- OISHII

- Articles

- Chefs Interview

- Rolling With Sushi Masters

Articles

Chefs Interview

Apr 1, 2014

Rolling With Sushi Masters

With the increasing popularity of sushi joints here, it’s no news that Singaporeans are a sushi-eating bunch. But what is it about sushi that makes it an islandwide favourite? And how do you tell a good sushi from a bad one?

Contrary to popular belief, sushi did not originate from Japan. Said to have its beginnings in Southeast Asia then spread to south China between 3rd and 4th century BC, it was only introduced to Japan during the 8th century. But as with some of the Japanese delicacies we are so familiar with today, even though sushi isn’t an indigenous Japanese dish, what the locals improvised and reinvented centuries ago made sushi a creation the country can proudly call its own.

The original form of sushi, nare-zushi, was created as a method to preserve fish using fermented rice. Fish was – and still is – an important source of protein, and it was left to ferment along with rice for three months to a year before it was consumed. The rice, however, was discarded. This method of preserving fish later spread throughout South China, before it was finally introduced to Japan during the Heian period. Then, the dish underwent its first improvisation – rather than discarding the rice and fully preserving the fish, the Japanese ate the rice along with the partly raw fish (preserved for between one week to one month) so as to maintain its freshness. By the end of the Muromachi period, this dish had had a new name: namanare-zushi.

It was during the Edo period that the Japanese once more reinvented the dish for one that has since become unique to Japanese culture: haya-zushi. Rice was no longer used for fermentation purposes; it was mixed with vinegar and served with fish, vegetables and other dried preserved foods. Later in the early 19th century, when mobile food stalls peppered the streets of Edo (now Tokyo), nigiri-zushi was a popular fast food of choice among the locals. Like the basic form of sushi we see today, nigiri-zushi was made up of a slice of fish placed atop a bite-sized portion of rice. This dish gained nation-wide recognition after the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923.

In Singapore, the uptake of Japanese cuisine among the locals was slow at first, but it quickly gained a foothold in the late 1980s. According to Chef Shiraishi Shinji, owner of Shiraishi, there were only 36 Japanese restaurants when he first came to Singapore in 1982. When he returned in 1990, the number rose to 150. Today, there are over 800 of them, including more than 100 sushi joints. While sushi is enjoyed as an occasional meal in Japan, the burgeoning demand of sushi in Singapore is a clear indication that many locals here regard the dish as part of their everyday meal.

But would the fine art of preparing sushi become lost among the bevy of sushi joints popping up across the island? We speak to three sushi masters to find out more.

(photography Charles Chua/A Thousand Words Text Tan Lili)

Ronnie Chia,

director of Tatsuya

What is the secret behind the success of Tatsuya?

To me, the success of a business is akin to maintaining a happy marriage. A happy, healthy marriage is entirely dependent on both the husband and the wife; it’s about teamwork. Likewise, for any business to succeed, teamwork is key. I even came up with my own mnemonic for the word “team”: Together, Everybody Achieves More. Without a good team to lay as the foundation, there wouldn’t be a business. Another philosophy I live by is to be the jack of one trade, and master of one. The toughest part about businesses is maintenance. Many people have asked me to expand my business, but the way I see it, when I maintain the success of one restaurant, I also maintain the consistency of the quality the restaurant delivers.

Define good sushi – what goes into it?

It’s a total package deal. The quality of the ingredients plays a crucial role, of course, but it all starts with the chef. Pay attention to the way he prepares the sushi – the passion with which a good chef prepares the dish is almost palpable, and which will also give rise to excellent service and sense of hygiene. The cutting technique has got to be precise as well; I reckon this is the utmost important skill every sushi chef should possess, yet only a few have genuinely perfected it.

What do you look out for when you train someone to become a sushi chef?

I am very selective with chefs. Apart from the prerequisite dedication, good sense of hygiene and culinary skills, they have to maintain a high level of professionalism and, most importantly, have a positive attitude. As sushi chefs, we have to constantly interact with our clients, who largely consist of macro- and micro-decision makers. Without a good attitude – both professional and personal – it takes away our promise of an all-encompassing dining experience from our clients.

Tatsuya

22 Scotts Road, Goodwood Park Hotel, Tel: 6887 4598

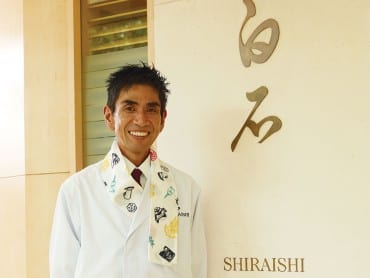

Shiraishi Shinji,

head chef and owner of Shiraishi

Can you share with us your secret to creating good sushi?

The steps to making sushi are actually really simple, but good sushi lies in how you prepare it. The temperature of the rice has got to be just right. When I hold it in my hand, the temperature should be as close to that of my body as possible. As a sushi chef, you have to be able to feel every grain of rice in your hand. At the same time, you have to make sure the rice contains the right amount of air as I mold the rice so its texture is consistently light and fluffy in your mouth. But the most important aspect of good sushi is the heart – when a chef doesn’t put in 100 percent of his mind and energy into making sushi, you will be able to tell from not just the way he prepares the sushi but also the taste of it. I put my heart into making each and every sushi; it is my dedication to my craft.

Your approach to making sushi is obviously very different from other sushi chefs. Besides your strong level of commitment, what are some of the other areas unique to Shiraishi?

The cutting technique I use is something you’d be hard-pressed to find in other restaurants. Many sushi chefs slice the fish in one angle – slanted – but the proper cutting technique involves a constant change in the direction with which you slice the fish, based on the part of the fish you’re serving. There is also a certain rhythm I developed in the assembly of the sushi. Usually clients might not see it, but I try not to touch the fish as much as possible. I’ll let you in on one more secret: the fingerbowl I use consists of part vinegar and part water, which is a mix almost similar to that used in sushi rice. This helps maintain the consistency of flavours in the final product.

What are some of the challenges a sushi chef-in-training would likely face?

To become a trained sushi chef, many chefs would say it’d take between five and 10 years. But to be honest, to be a true sushi master, it can take 10 to 15 years. One of the main challenges lies in mastering the cutting technique. The chef-in-training probably wouldn’t even get to touch the knives during his first year of training! When he eventually gets to use the knives, he usually starts by cutting vegetables like cucumber and white radish before moving on to small fish and, later, bigger ones. Another reason why the training takes so many years is because of the use of seasonal ingredients in Japanese cuisine. This means, in order for you to serve the freshest in-season ingredients, you would have only two weeks to prepare/cook them. In other words, since the ingredients would be available in the market for only two weeks a year, you’d have to wait for the next year to get another batch of fresh seasonal ingredients. It’s all about accumulative experience.

Shiraishi

#03-01/02 The Ritz-Carlton, Millenia Singapore,

7 Raffles Avenue, Tel: 6338 3788

Kenjiro Hatch Hashida,

master chef and owner of Hashida Sushi Singapore

You seem to take pride in the way you style your dishes, from the meticulous arrangement of the food to the added floral touches. Is art an important element to you?

Yes. In fact, my passion was in painting when I was younger. Even though I was helping my father at the restaurant, I had wanted to be a painter. I tried selling my artwork but it wasn’t very successful. When I was around 19 years told, I thought to myself, “Maybe I would be able to sell my paintings at higher prices if I became a famous chef!” Of course, later on I fell in love with a new art form: sushi-making. It also involves creativity, in that I have to constantly come up with fresh ideas for the dishes and the way I present them.

Define a true sushi master.

Someone who isn’t me! Despite my title, I believe I am still training to be one. It’s a continuous process – there is no end-date. I was 22 years old when I made my first sushi for customers. After taking a bite, one customer told my father, “I do not want to eat sushi prepared by a part-time chef.” My father discarded the sushi I made and prepared a fresh set for the customer, before revealing that I am his son. Of course the customer was taken aback and even tried apologising, but my father insisted the customer was right, that I did need the training. I really appreciated that my father did not give me any special treatment just because of our relationship – it’s taught me a great lesson in humility.

What sets Hashida apart from other sushi restaurants?

Our clients often rave about the rice we use, asking us what special ingredients we add to the flavouring. We never disclose the secret, of course – only my father and I are privy to the recipe of our rice. The way we present our dishes is also pretty unique. I am stoked that I can incorporate my love of art into sushi-making, in the way I style the dish.

With so many smaller sushi joints on the rise, do you think the market is getting saturated?

I never think of it as a competition, to be honest. From my perspective, we are all helping to bring the Japanese culture into Singapore; from a customer’s point of view, trying out different sushi bars feels almost like a source of entertainment. It’s definitely a win-win situation.

Hashida Sushi Singapore

#02-37 Mandarin Gallery, 333A Orchard Road, Tel: 6733 2114